West Mongolia Journey | Kharkhiraa Turgen Trek, Sand Dunes, Lakes & Nomads

Explore Mongolia, the incredibly diverse, sublimely beautiful ‘Land of the Eternal Blue Sky’, on an epic journey in western of Mongolia, including a Kharkhiraa + Turgen Mountains trek, the trip specially crafted for Kamzang Journeys. Our Western Mongolia trip is a one of a kind trip to Mongolia, led by Mongolian guides and experts. A seasoned travel writer once told me that his soul left his body to enter the rich earth of Mongolia …Mongolia is a remote Central Asian land of boundless space and sky, endless golden steppes, sparkling lakes and rivers, shifting sand dunes, a cradle of nomadic people and their horses, a land of diverse ethnic groups and sublimely beautiful landscapes.

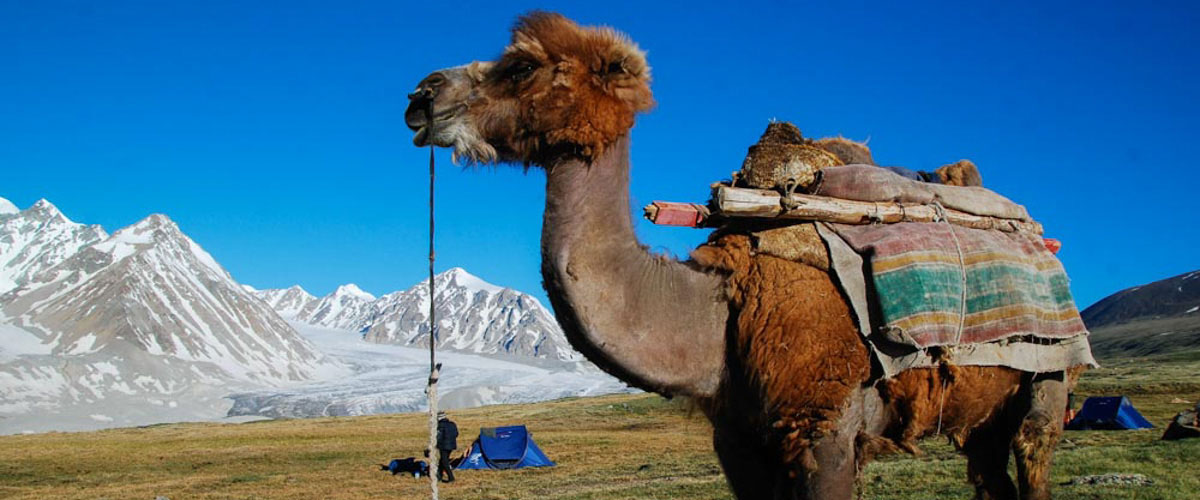

Steeped in legend, mythical Mongolia is the fabled land of Gengis Khan who conquered much of the modern world, of nomads on horseback, eagle hunters, felt gers backed by snow capped peaks, Bactrian camels, rare wildlife and both Shamanistic and Tibetan Buddhist traditions and monasteries.Our Mongolia journey features a great trek in the Kharkhiraa mountains, the world of the Kazakh nomads, journeys through desert and sand dunes, visits to nomadic gers, where Mongolians herd their Bactrian camels, photographing Mongolia’s eagle hunters and experiencing their unique way of life, Mongolia’s beautiful mountain lakes, rivers and snow peaks, hiking in the Tsambagarav National Park, otherworldly sand dunes, wild horses, exploring Buddhist monasteries and more!

Our Mongolia trip does it all in style, staying at atmospheric ger camps, camping and eating with nomads as well as in our comfortable camps. The driving is structured so that we see the maximum amount of the diversity of Mongolia, with lots of free time interspersed for hiking, exploring, visiting Mongolians in their gers and photography. Add on a trip to the Gobi Desert! Join us for our adventures in Mongolia!

NOTE | You must be booked on the trek – with flights booked and deposits paid – to get an invitation to Mongolia for your Mongolia visa.

Trip

West Mongolia Journey | Kharkhiraa Turgen Trek, Sand Dunes, Lakes & Nomads

Day 1 – Saturday, 6 June 2020 – Arrive Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar | Ulan Bator)

Day 2 – Ulaanbaatar | Sightseeing

Day 3 – Fly Ulgii | Drive Tsambagarav Mountain + Eagle Hunter Homestay

Day 4 – Tsambagarav National Park | Hiking, Riding + Nomadic Experience

Day 5 – Drive Uvs + Kharkhiraa Mountains | Achit Nuur + Uureg Nuur (Lakes)

Kharkhiraa & Turgen Mountains Trek

Day 6 – Trek Zuun Salaan Belchir

Day 7 – Trek Khujirt

Day 8 – Trek Turgen Camp

Day 9 – Trek Khiisen Khar

Day 10 – Trek Irvest Am

Day 11 – Trek Tel Mod

Day 12 – Extra Trek Day

Lakes, Sand Dunes, Camels & Nomadic Life

Day 13 – Drive Ulaangom + Khyargas Lake | Ger Camp

Day 14 – Khyargas Lake

Day 15 – Drive Mongol Els Sand Dunes Camp

Day 16 – Mongol Els Sand Dunes Camp

Day 17 – Drive Mukhart Sand Dunes Camp

Day 18 – Drive Senjit Khad + Khar Nuur Lake Camp

Day 19 – Khar Nuur Lake Camp | Nomadic Family Visit + Kayaking

Day 20 – Drive Ulaistai

Day 21 – Fly Ulaanbaatar

Day 22 – Saturday, 27 June 2020 – Trip Ends

Kharkhorin Extensions

Drive Tovkhon Khiid Monastery | Kharkhorin

Erdene Zuu Monastery | Khogno Khaan + Uvgun Khiid

Drive Ulaanbataar

Itinerary

West Mongolia Journey | Kharkhiraa Turgen Trek, Sand Dunes, Lakes & Nomads

Day 1 – Arrive Mongolia (Ulaanbaatar/Ulan Bator)

Welcome to Mongolia! The guide and driver will meet you in the arrivals hall at Ulaanbaatar Chinggis Khan Airport. Transfer to the hotel and check into your room. The plan for today is quite flexible, as arrival times may differ between group members, and you will probably want some downtime to relax and catch up on sleep. You may also need to sort out exchanging money and other practical things, and might want to wander out to visit some of the local markets.

Ulaanbaatar, meaning ‘Red Hero’, was so named in 1924, following the creation of the Mongolian People’s Republic. The city was founded in 1639 as a moveable Buddhist monastic centre but in 1778 it settled permanently at its present location on the Tuul River in north-eastern central Mongolia. The city lies at an elevation of about 1,310 meters and is home to almost half of the country’s 2.7m population.

Day 2 – Ulaanbaatar/Ulan Bator | Sightseeing

A free day with guided sightseeing to some of UB’s monasteries and historic sights. Sightseeing will include Ganden Monastery, the National Museum, Sukhbaatar Square, Winter Palace of Bogd Khaan and Tumen Ekh music ensemble. Lunch and a welcome dinner at one of our favorite Mongolian restaurants are also included in this full day of touring! (B, L, D)

Day 3 – Fly Ulgii | Drive Tsambagaray Mountain + Eagle Hunter Homestay

Transfer to the airport for your three-hour flight to Ulgii. (On private trips your UB guide will check you in and you’ll meet your local guide out west). Once in Ulgii we’ll have a chance to visit the local bazaar and museum. Ulgii is the capital of Bayan-Ulgii Province, 1645km from Ulaanbaatar, an ethnically Kazakh city whcih feels more like Muslim-influenced Central Asian than Mongolia. There are signs in Arabic and Kazakh Cyrillic, the market is a bazaar rather than the Mongolian ‘zakh’ selling kebabs (shashlyk) and stocked with goods from Kazakhstan

After wandering through the bazaar we board our private vehicles and drive southwest for two hours (90 km) to an open valley below Tsambagarav Mountain where many Kazakh nomads make their summer camps. We stay in specially set up gers next to our local contact, Sailau and his family. Sailau is one of the most celebrated eagle hunters in the area, and featured in the BBC’s Human Planet series. His son Berik continues the family tradition.

Although not the hunting season, we will be able to see Sailau’s eagle and learn about the traditions of hunting with eagles. There will be an opportunity to go for a walk in the surrounding area during the afternoon, before the family welcomes us into their home for a traditional feast of Beshparmak in the evening. We stay the night at the simple guest ger next to Sailau’s family’s ger. (B, L + D)

Day 4 – Tsambagarav National Park | Hiking, Riding + Nomadic Experience

After breakfast, we set off up the hill towards the upper glacial valleys of Tsambagarav, pass by a waterfall, and hike into a lush green valley in the shadow of the glacier of Tsast Uul. There are generally many nomadic families in this area although earlier trips will have the remote countryside to themselves. We’ll picnic en route and return to the family’s ger encampment in the afternoon.

There will also be an opportunity to help in the daily life of the local nomads – milking animals, preparing dairy products, cooking, and watching how they weave their embroidered Kazakh hangings. You may also have a chance to erect a ger, with some help from the locals of course!

Tsambagarav is an area between Khovd Province and Bayan-Olgii Province in western Mongolia, and forms part of the Altai Mountain range. It has two peaks – Tsambagarav (4208m) and Tsast (4193m). The National Park area covers more than 1110 square kilometers. Known for its stunning vistas and diverse wildlife, it contains many glaciers, rocky gorges, glacial lakes, and a 7 meter waterfall, in addition to deer stones, balbal (standing stones), and Kazakh and Uriankhai nomads. Many rare and endangered species can be found including the argali sheep, ibex, snow leopard, rock ptarmigan and Altai snowcock. The area is a great place for hiking, horse riding, mountain climbing, fishing, and hunting with eagles. We spend another night with Sailau and family. (B, L + D)

Day 5 – Drive Uvs + Kharkhiraa Mountains | Achit Nuur + Uureg Nuur (Lakes)

Today we drive to the country’s most northwesterly province, Uvs, stopping en route at Achit and Uureg lakes. The destination is a rural area set in the hills beneath the Kharkhiraa mountains, a beautiful spot and ideal for exploring the surrounding area. We reach Tenuugiin Am, a valley of the Kharkhiraa mountain range where we start our trek tomorrow, after approximately six hours of driving (210 km). We’ll also meet the pack camels and local mountain guide/wrangler who will guide us on the trek

Uvs Province lies in the Great Lakes Depression in the North-West of Mongolia. 60 percent of its area is ‘Khangai’ (hilly with a pleasant climate, fertile soil, forests, rivers and lakes) while the other 40 percent encompasses the Gobi region. Uvs is a province of high mountains, part of the Altai Range – Kharkhiraa, Turgen, Tsagaan Shuvuut, Yol yamaat, Zest. The highest point is Kharkhiraa peak, at 4037m. There are also many lakes in the province, such as Khyargas, Khar Us, Achit, Uureg and Uvs, the latter the largest lake in Mongolia at 1293 square miles. The aimag is famous of historical and cultural sights, such as stone figures, various types of rock drawings. Wildlife is represented by antelope, black tailed antelope encountered in the meadows of Khyargas, Kharkhiraa and the Uvs lakes. Deer, boars, wild sheep, ibexes, snow leopards, martens, and wolverines are found in the Khankhukhii, Kharkhiraa and Turgen mountains, while marmots, badgers, foxes, wolves are found mainly in the hills and valleys. (B, L + D)

Kharkhiraa + Turgen Mountains Trek

Over the following 6 days we’ll trek for approximately 6 to 7 hours a day, covering between 20 and 30 kilometers each day depending on the terrain and gradient, the altitude ranging from 2000 to 3250 meters. Along the way we’ll have a chance to visit nomadic families and experience traditional Mongolian hospitality. Pack camels will carry tents and camping equipment, including a dining tent, our cook tent, our personal tents and a toilet tent that doubles as a hand-pump shower cubicle. (B, L + D)

Day 6 – Trek Zuun Salaan Belchir

We start the trek hiking through the Tenuugiin Am valley, following the river. We’ll need to cross the water several times, and in places where the current is strong you’ll need to hop on the back of the cook or wrangler’s horse to do this! In the afternoon arrive at your camp spot at Zuun Salaan Belchir.

Day 7 – Trek Khujirt

Continue your trek up to the Uliastai mountain pass – from the top you will have a beautiful view of snow peaked mountains of Kharkhiraa, green valleys and lakes. Walk down the mountain and have a picnic lunch at Khukh Nuur (Blue Lake). Continue on trekking along the lakeside to the next camping spot near to Khujirt, center of local rural nomadic community.

Day 8 – Trek Turgen Camp

We continue to trek through the valley, crossing another pass called Gyalsah. On the way, we’ll have to cross the Delger River. We will be passing beneath Kharkhiraa (4037m) and Turgen (3965m) Peaks, the highest snow covered peaks of Turgen Mountain range. En route we will have a chance today to visit nomadic families and taste traditional dairy products.

Day 9 – Trek Khiisen Khar

Today is the longest day of our Kharkhiraa and Turgen Mountains trek. In the morning we cross the Kharkhiraa River, continuing to trek to Olon Nuuriin Belchir, a valley of numerous small lakes, all fed by rain water and underground springs. Some years, depending on the rain, the number of lakes reach 80 or so. Today’s route sticks to the lower slopes of the landscape, since the flat area is quite boggy. Stay overnight around Khiisen Khar.

Day 10 – Trek Irvest Am

Today we hike over Ereesen pass to the Yamaat river to reach our camping spot Irvest Am (meaning narrow mouth/valley) in the shadow of Yamaat Mountain, an area renowned for its ibex. We should see a wide variety of fauna in this area; your guide will keep an eye out for interesting flora and fauna.

Day 11 – Trek Tel Mod

We trek along the mountain valley and cross the Yamaat river three times with the help of a horse to arrive at the incredible ancient rock painting and burial sites that can be found in this area. This evening the vehicle will come to meet up with the group at the campsite near Tel Mod.

Day 12 – Extra Trek Day

A free day to explore one of this treks beautiful campsites, and to spend some more time visiting the many nomadic settlements in this region. Or an extra trek day in case of weather issues.

Lakes, Sand Dunes, Camels + Nomadic Life

Day 15 – Drive Ulaangom + Khyargas Lake Camp

After breakfast we set off by private vehicle to Ulaangom, the provincial town of Uvs province. The roads today are quite good, which will make for a comfortable change for our four hour (210 km) drive! On the way stop at Ulaan Davaa (pass), from where we’ll have a good view of Deglee Tsagaan Mountain. A bit further on we stop to view the snow-capped peaks of Kharkhiraa and Turgen.

In Ulaangom, we visit the local museum and have lunch, and you may also want to visit the local market. The nearby Ulaan Uul Mountain is a significant place of ethnography where 54 tombs of the pre-Tureg period are located. On arrival at Khyargas lake, we settle into our ger camp on the shore of the lake. Take a stroll around the area, renowned for its abundant bird life in the summer months.

Khyargas Nuur National Park, based on a salt lake amid desert and scrub grass, provides an attractive summer home for birds. It is renowned for the Khetsuu Khad, an enormous rock on the south side of the lake, that attracts migratory cormorants. The birds arrive in April and hatch their young in large nests built on the rock. The aura created by the white cliffs, shrill birds and the prevailing smell of guano makes you feel as if you’ve arrived at the ocean. By mid-September the cormorants are off, migrating back to their wintering grounds in southern China. We stay in gers at either Khar Temistei or Khetsuu Khad Ger Camp. (B, L + D)

Day 16 – Khyargas Lake Camp

This is such an incredible site that it’s worth an extra day to swim in this refreshingly cool lake, photograph the cormorants and their artistic nests, and soak in the unique atmosphere at all times of the day!

Mongol Els + Mukhart Sand Dunes | Camel Riding | Senjit Khad + Khar Nuur

Over the next three days we explore the large area of sand dunes that run to the south of the Zavkhan River, known as Mongol Els, camping as we go, a sublime experience! We may have a chance to ride some camels on the dunes depending on where the camels are, and whether they’re ‘tame’ enough!

Day 17 – Drive Mongol Els Camp

We depart Khyargas Nuur after breakfast and continue to drive east for approximately four hours (200 km), making camp on the edge of the dunes as we begin a series of night’s camping in the wilderness. In the afternoon head off on a unique dune walk with the guide. (B, L + D)

Day 18 – Mongol Els Camp

As yesterday’s drive was a long one, it’s worth an extra day to wander through this incredible region of flowing sand dunes, with plenty of time at sunrise and sunset for photographing this unique desert region, with its passing caravans of camels!

Day 19 – Drive Mukhart Sand Dunes Camp

On the second day we drive for three hours (130 km) to reach the Mukhart sand dunes and camping beside the river that runs from the foot of one of the huge sand dams and meanders through the sand dunes forming green oases as it goes. You can hike to the top of the dunes and slide down, plus walk in or along the water where it is shallow. We will find a nice camping spot where the golden reeds form a natural wind barrier. (B, L + D)

Day 20 – Drive Senjit Khad + Khar Nuur Camp

On the third day of our sand dunes trip we drive for three hours (100 km) via Senjit Khad, a natural stone arch situated on an elevated plain. You can spend some time exploring and climbing these natural rock formations which also give amazing panoramic vistas of the surrounding landscape. We then reach the blue lagoon of Khar Nuur, surrounded variously by sand dunes, glacial rock formations, plateaus, grasslands. Khar Nuur, meaning ‘Black Lake’ in Mongolian, is located 80km to the northwest est of Uliastai, and is around 27km long and 6km wide. It occupies a dale between the Khangai Mountains to the East and the Great Lakes Depression to the West. Surrounded by swathes of sand dunes, the area is stunning and remote. (B, L + D)

History of Camels

About 285,000 Bactrian camels – 30% of the world’s population – live in Mongolia, mainly in the Gobi desert. Camels are powerful animals, standing over 2 metres tall at the hump and weighing 720-820kg. A camel can haul loads of nearly 300kg at a rate of 50km per day. Although averaging 4km/h, they have been clocked at over 65km/h. Well adapted to harsh climates, camels are famous for their ability to travel as many as 160kms without water. They retain their body moisture efficiently, and have a large capacity for storage. A thirsty camel can drink as many as 135litres at a 10minute sitting. They don’t store water in their humps – these conserve up to 36kg of fat, which allows the camels to survive when food is scarce. The humps shrink as fat is consumed for energy.

Day 21 – Khar Nuur Camp | Nomadic Family Visit + Kayaking

A rest day to explore this sublimely beautiful area. Those who would like to can do some kayaking, and there will also be an opportunity to visit local nomadic families and go walking in the surrounding areas, which include a nearby canyon. (B, L + D)

Day 22 – Drive Uliastai | Zavkhan Province

Today we drive three hours (120 km) to Uliastai, the capital of Zavkhan province. Surrounded by mountains, with a river and lush valleys, the town has a relaxed feel to it. Spend some time visiting the local history museum, and its sister ‘Museum of Famous People’ – well, famous to Zavkhan Province at least! The province also boasts a rich Buddhist heritage, with 9 of the 11 Mongolian Bogd lamas coming from the province. A visit to the hilltop stupa complex of Javkhlant Tolgoi, surrounded by statues of elk, ibex, and argali sheep, is absolutely worth a visit. Additionally, we’ll visit the neighboring temple and museum of Togs Buyant Javkhklan, a quick hike from the center of town and offering a good panorama of the city. Uliastai is also renowned for Morin Khuur (horse headed fiddle) and tonight we shall arrange for a private demonstration, lesson and performance to the group by some local musicians.

Uliastai is the capital of Zavkhan Province, one of the most remote aimags in Mongolia. Alongside Khovd, Uliastai is one of the oldest settlements in Mongolia, and was connected by camel caravan routes with Urga (now Ulaanbaatar) in the east, Khovd in the west, and Chinese cities to the south. The city was founded as a military garrison by the Manchus in 1733 during the Qing rule of Mongolia. Uliastai was the de facto capital of Outer Mongolia, as the Qing Amban, the Governor General, located its office in Uliastai to keep eye on the Khalkh Mongols to the east and the Oirat Mongols west of the Khangai mountains.

Zavkhan covers a wide area of mountain, steppe and desert in the remote central-western part of Mongolia. The aimag borders with Khovd and Uvs in the west, the Tuvan Republic of the Russian Federation in the north, Khuvsgul and Arkhangai aimags in the east, and Bayankhongor and Govi-Altai aimags in the south. The rugged terrain includes the highest of Khangai Mountain range – the sacred peak of Otgontenger (4031m). The western part of the aimag is occupied by steppe and dunes. Zavkhan also has over 200 springs and rivers, and over 100 lakes.

We stay at a recently opened guesthouse, the Fat Yak, run by one of our most experienced guides, Tudevee, who is local to the area. He has recently returned to the area of his birth to set up the guesthouse. You will enjoy a welcome hot shower after the days of camping, and a comfortable bed. In the evening enjoy some traditional delicious food prepared by local chefs. (B, L + D)

Day 23 – Fly Ulanbaatar

Depart for flight back to Ulaanbaatar. We will get back in time to do some shopping, perhaps at the Gobi Cashmere outlet store, and also at any of the decent craft outlets (Tsagaan Alt felt shop, Quilters, Mary and Martha) or the State Department Store. Your guide will be on hand to assist. After freshening up at the hotel, we’ll enjoy a farewell meal at one of our favorite restaurants.

Day 24 – Trip Ends

Transfer to the airport for your flight home. (B)

Highlights & Reviews

Kamzang Journeys Reviews

Read More Testimonials

Trekkers’ Comments

Trip Highlights

- Kharkhiraa Mountains Trek in Western Mongolia

- Eagle Hunters

- Kazakh Nomads, Mongolian Gers + Bactrian Camels

- Mongolia’s Sublimely Beautiful Mountain Lakes + Rivers

- Breathtaking Mongolian Steppe, Desert + Mountain Landscapes

- Tsambagaray National Park

- Buddhist Monasteries

- Traditional Mongolian Ger Camps

- Green + Beautiful Campsites with Late Summer Evening Light

- Very Qualified, Ecologically Friendly + Environmentally Concerned Staff + Mongolian Agent

- An Epic Road Trip

- Mongolia’s Endless Sky …

Kim Bannister Photo Gallery | Trip + Trek Photos

Kim Bannister Photography

Kamzang Journeys | Country + Regional Photos

Kamzang Journeys Photos

Travel Reading | Enhance Your Trip!

Travel Books

Monglia Articles

Tim Cope: On the Trail of Genghis Khan | National Geographic

Mongolian Diptychs | NYT

The Trail of Genghis Khan | Screen Australia – Tim Cope’s Ride across Mongolia

Teenage ‘Eagle Huntress’ Overturns 2,000 Years Of Male Tradition – NPR

Mongolian Throat Singing – YouTube Music Video

How China’s Politics of Control Shape the Debate on Deserts – New York Times

Mongolia, Land of Lost Opportunity – Wall Street Journal

Mongolia’s Mangled Politics – Foreign Affairs

A Documentary Star is Born: The Girl Who Hunts with Eagles – Film Preview

How Your Cashmere Sweater Is Decimating Mongolia’s Grasslands – NPR Audio

Frozen Tombs of Mongolia | YouTube Video about Scythian Tombs in Western Mongolia

Genghis Khan | BBC YouTube

I Have Seen the Earth Change | YouTube

Nomads of Mongolia | Brandon Li Vimeo

Winter in Mongolia | Jonathan Stewart YouTube

In Mongolia, a Changing Nomadic Way of Life | Radio Free Europe YouTube

Mongolia’s Dilemma: Who Gets the Water | NPR

Fascinating Photos of Reindeer People Living in Mongolia | My Modern Met

Herding Reindeer | Joel Santos Photos, Huffington Post

Tracking the White Reindeer | Hamid Sardar-Afkhami

Life Among the Reindeer People | NPR

Saiga Antelopes are Struck Again by a Plague in Central Asia | NYT

Teenaged Mongolian Eagle Hunters | Foreign Correspondent

Why Ghengis Khan’s Tomb Can’t be Found | BBC

Mongolia’s Obession with Pine Nuts | BBC

The Singular Beauty of Mongolia Through a Photographer’s Eyes | AFAR

How a Mongolian Heavy Metal Band Got Millions of YouTube Views | NPR

Mongolia, the Last Eagle Hungers | Al Jazeera 101 East

Mongolia Eagle Hungers | Red Bull Video

On the Trail of Ghengis Khan | ABC (Australia Only)

Photographs of Mongolian Eagle Hunters | Designs You Trust

Kim Bannister Photo Gallery | Trip + Trek Photos

Kim Bannister Photography

Travel Reading | Enhance Your Trip!

Travel Books

Date & Price

2020 Dates

6 – 27 June

22 Days

Trip Price

$4780 (10+ Travelers)

+ $5080 (8+ Travelers)

+ $5680 (5+ Travelers)

+ Deposit $1000

+ Single Supplement Ger Camps + Hotels – $

+ Extra Nights UB Hotel Room S | D – $90 | $130+ NO Single Supplement for Camping

Includes

- Hotels, Ger Camps, Guest Houses in Mongolia

- All Meals

- Trek

- Transport by Private Vehicle

- Airport Transfers

- Domestic Flight

- Entrance Fees + Permits

- Single Tents on Trek

Excludes

- International Flights

- Travel Medical + Travel Insurance (both required)

- Mongolia Visa

- Helicopter Evacuation

- Alcohol, Sodas & Packaged Drinks

- Tips

Tips & Extra Cash

Allow approx $250 for meals (while not on trek), drinks (on trek) and tips. We recommend $250-$300 per trekker thrown into the tips pool for the crew.

Contact & Details

Guide

Ade Summers + Mongolian Guide

Kamzang Journeys Contact

Kim Bannister

kim@kamzang.com

Mobile: +(977) 9803414745 (WhatsApp)

On-Trek Satellite Phone: +88216 21277980

On-Trek Satellite Phone: +88216 21274092

Contact Numbers in Mongolia

+ Guide (Details on Booking)

+ Ulaanbaatar Hotel (+976 11 320620)

+ Mongolia Office (Tuul: +976 9989 1826. Please note that you cannot leave voice messages on this number)

+ UK Office (Olly Reston: +44 (0) 1869 866 520. You can leave voice messages if necessary, and these are checked regularly)

InReach Explorer

We have a MapShare page that works for sending emails to our InReach messaging device. Give this link to people who want to follow us and have them send us a message so we have their email in the system. We can email them back directly Please tell people not to expect updates every day. There is a ‘message’ button on the top left, and the message sender needs to put their EMAIL address instead of phone number to get a response. Messages are free, enjoy.

Follow Us on Facebook

Kamzang Journeys Facebook

I will post InReach updates to our Kamzang Journeys Facebook page if friends & family want to follow our progress.

Satellite Phone

We carry a satellite phone with us for emergencies. Send us a free message at the online Thuraya link below. We can call you back or email you back. If you want a return call or email include your contact info. You can send this in two SMSs if needed.

Kim Satellite#1: +88216 (21277980)

Kim Satellite #2: +88216 (21274092)

Lhakpa Satellite: +88216 (87710076)

Thuraya Message Link

Mongolia Contact

Details on Booking

Ullanbatar Hotel

Ulaanbaatar Hotel

Mongolia Visa

Mongolia is a country that requires many foreign citizens to have obtained a visa in advance of travel. A Mongolian tourist visa is usually valid for a stay of up to 30 days, with entry within three months from the date of issue. It is your responsibility to ensure you have a valid visa to travel to Mongolia, if required, according to your nationality. Please note that all UK, Australian and most European citizens (excluding Germans) DO require a visa to travel to Mongolia, and this must be applied for in advance – usually at any country’s Mongolian Embassy or Consulate (whether you are a citizen or resident of that country or not). Only in exceptional circumstances may it sometimes be possible to pre-arrange a visa on arrival.

Exempt Countries

USA, Canada, Germany, Russia, Turkey, Japan, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Brazil, Israel, Philippines, Cuba, Hong Kong and Singapore

+ These countries do have rules and regulations associated with length of visit, please check before travel.

How to Apply

Obtaining a visa is a straightforward process, and usually very quick – especially if you are able to apply in person. Most embassies will return the visas within 2-3 days for a standard service, and some of them offer a same day express service. Most embassies require minimal documentation – the 2-page application form; passport valid for at least 6 months after date of entry and with at least 1 blank page for the visa; fee payment; passport photo. Some embassies ask for additional documentation – an itinerary, flight reservation, a letter of invitation from your tour company (i.e. us) – so please check. We can usually help provide all additional documentation.

Filling out Visa

There are some sections of the form that you may require help with. Please fill in as follows:

+ Name and address of host person or organisation in Mongolia: Goyo Travel, Door 1A, Tower A, Golomt Town, Peace Avenue, Ulaanbaatar; Tel. 9959 8468

+ Your home address and telephone number in Mongolia: Ulaanbaatar Hotel, 14 Sukhbaatar Square; Tel. 320620

Monglian Embassy Websites

UK USA Australia France Germany Hong Kong Singapore

Some embassies have an online application form on their website, and sometimes the functionality is poor or confusing. Please be aware that embassies also accept hand-written forms, and there is one standard form worldwide.

Mongolian Visa

Customs + Immigration

There are only six border points open to most foreign passport holders. They are at Chinggis Khaan International Airport in Ulaanbaatar, the road and train crossing to China at Zamyn Uud, the road crossing to Russia at Tsagaannuur in the far west, the train crossing to Russia at Sukhbaatar and the road crossings to Russia at Altanbulag and Ereen-Tsav in the north east. You may not cross into China or Russia at any of the other border points as they are either seasonal and/or are open only to Mongolians and/or Chinese and Russians.

Foreigners on a tourist visa are legally required to carry their passports at all times. Failure to carry your passport may lead to a fine, and officially a photocopy is not sufficient – however in our experience checks are very seldom, and in reality passport copies are fine (so many of our guests leave their passports at the hotel when in Ulaanbaatar; or in their gers/bags in vehicles when out in the countryside). We recommend that whatever you do, you should keep separately and somewhere safe, a copy of both the bio data page in your passport and your Mongolian border immigration stamp. This will help you both to obtain a new travel document and to demonstrate that you entered Mongolia legally should you lose your passport.

If you intend to remain in Mongolia for more than 30 days or if you do not have an entry or exit visa, you must register your stay with the Mongolian Immigration Agency in Ulaanbaatar within a week of arrival. You can appoint someone to do this on your behalf if necessary.

+ Goyo Travel offer this service if required.

Health Information

Mongolia Health InformationCDC

Travel Health WebsitesTravel Doctor Info + MD Travel Health

No special inoculations are required for travel to Mongolia but you should be up-to-date on standard vaccinations (Tetanus, Diptheria and Hepatitis A). Please consult your doctor 4-6 weeks prior to travel.

+ Rabies. The chances of being bitten in Mongolia by animals that could carry rabies are relatively slim. This low risk, combined with cost and lead-time for pre-vaccination, and the fact that pre-bite vaccination only reduces the number of post-bite vaccinations needed rather than preventing the contraction of the disease, mean that most people don’t bother. In the unlikely event that you are bitten and are not vaccinated against rabies (most people aren’t), then you can rest assured that on almost all trips you will be able to access the required first injection within the recommended 24hr post-bite period. An injection within 24 hours is required whether or not you have had the vaccination beforehand – the difference is that pre-vaccinated people have 3 injections in advance, and 3 after the bite. Non pre-vaccinated people have 5 injections after the bite.

+ Encephalitis Japanese +/or Tick-born. Only specifically recommended if going to heavily forested regions (Khentii and Selenge province) which is unlikely.

Travel Medical Insurance

Required for your own safely. We carry a copy of your insurance with all contact, personal and policy information with us on the trek and our office in Kathmandu keeps a copy. Note that we almost always trek over 4000 meters (13,000+ feet) and that we don’t do any technical climbing with ropes, ice axes or crampons.

NOTE: We advise that you check with your insurance company that SOS Medica is on their list of approved service providers in case of an emergency that requires medical evacuation. If not, you can purchase extra cover locally.

Medical Emergencies

+ First Aid – In case of an accident that requires administering of First Aid at the scene, our staff are trained in basic emergency response techniques, and all trips carry LifeSystems first aid kits, equipped according to the nature of the trip. We check, replenish and/or replace our kits on a regular basis.

+ Local Hospitals – For relatively minor injuries including cuts, sprains, dehydration, fractures etc., local hospitals will usually be able to provide adequate medical provision. In most instances you will be within 0-4 hours’ drive of a local hospital. Doctors here will probably not speak English, so your guide would translate.

+ Evacuation to Ulaanbaatar (and Abroad) – SOS Medica, in Ulaanbaatar, are part of a chain of international private clinics. They provide a helicopter medical evacuation service in partnership with A-Jet Aviation, and have English-speaking local and international medical staff. Their contact details and 24hr emergency number are in our ‘Trip Manual’, a copy of which is provided in each vehicle. On more remote trips that are equipped with satellite phones, their contact details are saved on the phone. For more information on SOS Medica, please visit www.sosmedica.mn.

Global Rescue

We recommend that our trekkers also sign up for Global Rescue, which is rescue services only, as a supplement to your travel medical insurance.

Book package through Wicis-Sports via Carlota Fenes (carlota@wicis-media.com)

Wicis-Sports Wearable Tech | Sports Package

Live personal heath stats via a wearable chest strap heart rate monitor.

Track your vitals (heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation), the weather, GPS locations, altitude, speed, bearing and stream LIVE via a Thuraya satellite hot spot. Partners: OCENS (weather), Global Rescue, Aspect Solar.

Thuraya Telecom + WiCis Sports offer connectivity to Himalayan treks + expeditions

“Founded in 2011 by Harvard and Stanford anesthesiologist Dr. Leo Montejo and located in the Lake Tahoe area, the company’s goal is to promote the use of mHealth and tracking devices to make adventure sports safer and engage their followers with real time data that is either private or also available to social medial platforms.”

Book package through Wicis-Sports via Carlota Fenes (carlota@wicis-media.com)

Medical

We have a full medical kit with us including Diamox, antibiotics, inhalers, bandages, re-hydration, painkillers, anti-inflammatory drugs etc. but please bring a supply of all prescription and personal medications. Kim has First Aid, CPR and Wilderness First Responder (WFR) certifications as well as many years of experience with altitude in the Himalaya but is NOT a qualified medic or doctor, so please have a check-up before leaving home, and inform us of any medical issues. This is for YOUR OWN safety.

DO bring all prescription medications and good rehydration/electrolytes. We advise bringing your own Diamox, Ciprofloxin, Azithromyacin & Augmentin. We have all of these with us but the Western versions are always better than the Indian equivalents.

Travel Books

Enrich your experience in Mongolia!

Travel Books

Arrival Mongolia

Arrival in Ulaanbaatar

The guide and driver will meet you in the arrivals hall at Ulaanbaatar Chinggis Khan Airport. Transfer to the hotel and check into your room. The plan for today is quite flexible, as arrival times may differ between group members, and you will probably want some downtime to relax and catch up on sleep. You may also need to sort out exchanging money and other practical things.

Arrival Hotel

Ulaanbaatar Hotel

+ Extra Nights – Single $90 | Double $65 (Per Person)

Arrival By Air

Ulaanbaatar’s Chinggis Khaan airport is small by international standards. Arriving and departing is usually a painless and relatively swift process.

+ Exit the plane and queue up at passport control counters marked ‘Foreign’. Usually there are 2 of them. This will take up to 30 minutes, depending on your place in the queue.

+ Then proceed downstairs to collect your luggage (there is only 1 carousel) before exiting to the arrivals hall.

+ After collecting baggage, you may be asked by customs officials to screen your luggage in a machine before exiting and/or check your luggage tags against the corresponding labels that you were given when checking in, to make sure you have taken the correct bags.

Departure by Air

+ Check-in 2 hrs prior to flight time is ample for all international flights

+ There is no departure tax to pay (all taxes are included in ticket prices)

+ Fill in a departure card and hand in at passport control counters after going through security

+ There are shops and cafes in the departure area near the gates.

Arrival By Rail | China

Passengers travelling by train across the China/Mongolia border at Erlian/Zamyn-Ud should expect a delay of a few hours because of the need to change the bogies, as the railways use different gauges. If travelling from Beijing to Ulaanbaatar on Train No. 23 you should expect the following

+ Arrival at Chinese border approx 8pm

+ Hand over passports and declaration forms (these are provided by attendants in advance), which are taken away and returned later.

+ You may or may not have the choice to stay on the train during bogie change. If you can ,or have to, stay on the train, please note that the loos will be locked.

+ If you can, or have to, leave the train this is for most people the preferred solution, but take a book/iPad/cards etc. You will be led into the station waiting room where there is access to loos and usually a small convenience store may be open. Don’t count on it though.

+ After 2-3 hrs you will get back on the train and passports handed back.

+ The train will move a short distance into Zamyn-Ud, the Mongolian border. Your passports will be taken again, and returned once checked.

+ You will finally be on the move again anytime between midnight and 2am, so do not expect unbroken sleep until then!

Arrival By Rail | Russia

No need to change the bogies, but the border crossings can take longer – up to 6-7 hours combined. Coming into Mongolia from Russia, you have to get off the train in Naushki whilst they uncouple carriages not going on to Mongolia. There is a station cafe, loos, and you can walk into the town if you want, although it is only worth it just to pass the time and to stretch your legs. Maybe 4hrs here, then back onto the train – more passport checks, no-mans land/border crossing, then 30kms the Mongolian border town of Sukhbaatar where it stops for an hour or so (get off and have a wander/drink if you want, or stay on train), and then you’re off.

+ Most trains arrive in Naushki around lunchtime and you’re off and rolling out of Sukhbaatar by around 9pm, arriving into Ulaanbaatar at 6am.

Flights to Mongolia

The number of flights and routes to Mongolia has increased significantly in recent years. The following cities have direct flights to Mongolia, and all are major international transit hubs providing connections to many countries. The flight frequency listed is based on summer schedule during June-Sep (winter schedules are often subject to reduced frequency).

Beijing – MIAT and Air China both fly direct daily

Frankfurt – MIAT fly direct 2 times per week

Hong Kong – MIAT fly direct 5 times per week

Istanbul – Turkish Airlines fly ‘direct’ 3 times per week (refueling en route!)

Moscow – Aeroflot fly direct daily; MIAT fly direct 2 times per week with connections from/to Berlin as well.

Seoul – MIAT and Korean Airlines both fly direct daily

Tokyo – MIAT fly direct 5 times per week

Extra Days in Mongolia

If you would like to visit the Gobi Desert or spend more time in Mongolia, let us know and we will help to make arrangements for you. Details and prices according to your specifications and time, but set aside at least five days for a Gobi trip.

Temperatures + Clothing

Mongolia has an extreme rages of climactic zones, ranging from the scorching, humid Gobi to the cold steppe. In general we visit Mongolia in the summer, so you can expect hot days while traveling across the country in jeeps, the usual mountain weather when trekking. Chilly in the evenings, gets hot during the day, can rain or snow. Think layers, bring a down jacket, down sleeping bag, sun hat, sunscreen, good sunglasses, light hiking shoes.

Ullanbaatar is casual, bring a pair or jeans and something light to wear out to dinner if you want. Nothing revealing outside of Ullanbaatar, in general. The Gobi is EXTREMELY hot, so bring lightweight and light colored clothing, sandals, sun hats and stay out of the mid-day sun!

In Mongolia

Temperatures + Clothing

Mongolia has an extreme rages of climactic zones, ranging from the scorching, humid Gobi to the cold steppe. In general we visit Mongolia in the summer, so you can expect hot days while traveling across the country in jeeps, the usual mountain weather when trekking. Chilly in the evenings, gets hot during the day, can rain or snow. Think layers, bring a down jacket, down sleeping bag, sun hat, sunscreen, good sunglasses, light hiking shoes.

Ullanbaatar is casual, bring a pair or jeans and something light to wear out to dinner if you want. Nothing revealing outside of Ullanbaatar, in general. The Gobi is EXTREMELY hot, so bring lightweight and light colored clothing, sandals, sun hats and stay out of the mid-day sun!

+ All information below from our excellent Mongolian agent! +

Climate

Mongolia is country of extreme weather patterns, with warm, short summers and long, dry and very cold winters. Known as “the land of blue sky”, Mongolia usually has about 250 sunny days a year – but the majority of these are between September and May. In the coldest winter months of December-February, some areas of the country drop to as low as -50°C , with Ulaanbaatar often seeing temperatures of -35°C. In the summer the Gobi basks in 30°C+ temperatures, whilst it’s colder the further North you go.

You might expect to see a chart of ‘averages’ in this section. Forget it – it’s irrelevant! At best it just shows you how cold it is in winter, and at worst it is misleading about what to expect in the summer.

If travelling between May and September, 4 seasons in 1 day is a distinct possibility, and 4 seasons during the trip is an absolute certainty. Anything is possible, from 30°C and no wind in May, to 15°C and snow in August.

There are, however, some distinct benefits about this changeable climate – bad weather often passes very quickly. And more often than not, the weather is good. Here is a quick overview of what to expect during the main travel months:

May – Dry, windy, dusty, sunny. Large fluctuations in temperature. Day 10-20°C; Night 0-10°C

June – First half similar to May, then temperatures rise and less fluctuation. More cloud cover, some rain. Day 15-25°C; Night 10-15°C

July – A mixed bag. Very changeable – sunshine most days, but also cloud and rain most days. Day 15-30°C; Night 10-20°C

August – First half similar to July, then it becomes a lot drier and sunnier, but colder at nights. Day 15-30°C; Night 0-15°C

September – Dry, sunny, calm, chilly. Day 0-20°C; Night -5 to +5°C

It is usually colder in the North and warmer in the South, as is to be expected. One thing is for certain: you will have to pack for all eventualities!

Packing

Think layers. Think casual. Think practical. Duffel bags recommended for easy packing and transport. Pack loose-fitting, lightweight cotton materials, the most comfortable for humid and warm conditions, thermals, fleece tops, fleece + fiber-filled jackets for colder conditions, waterproof + windproof jackets important to pack. Lighter colors for the desert.

Cultural Issues + Etiquette

Mongolian culture is rich in social tradition and even in modern times there are many everyday situations where there are accepted ways of doing things. This is particularly true in the countryside, where there is an additional set of codes associated with visiting a ger, and other rural nomadic customs. Respect and superstition lie behind almost all of them – respect for ones elders and for nature, plus superstition linked to the powers that shape the natural world, manifested through beliefs rooted in shamanism. There are also Buddhist elements to many practices.

Don’t worry though, no Mongolian will expect you to know many of their customs (if any at all) and most will delight in teaching you, including your guide. You will not insult people by making mistakes, but you might if you don’t learn from them!

Do’s

+ Pass with right hand

+ Shake the hands of someone who you have accidentally bumped feet with

+ Accept food or drink that is offered to you – if you don’t like it, at least be seen to try it before passing it on or handing it back

+ Accept vodka if served and passed round – dip your ring finger in, then throw a few drops to the sky, into the wind (to the side), and to the floor. If you don’t want to drink, you can still perform this ritual, then touch your forehead with the finger, and put the glass back on the table.

+ Proceed to the left as you enter a ger

+ Talk about death or bad things that might happen!

Don’t

+ Pass with left hand

+ Point with your finger

+ Point the soles of your feet to anyone when sitting

+ Talk or joke about bad things that may happen

+ Say thank you too much or for small gestures

+ Pass anything between or lean against the ger poles

+ Touch other peoples hats, let alone to sit or stand on one

+ Step on the threshold to a ger

Gifts

Mongolians are renowned for their hospitality and generosity – particularly in the countryside. You will visit nomadic families during your trip – which may occur once or twice, or may be a daily occurrence, depending on your itinerary and personal preference. Locals will not expect anything in return for their hospitality – it is a natural, cultural tradition to welcome passing travellers into their home and offer tea, food, snuff, vodka etc. However, it is perfectly appropriate to offer gifts as a small token of your appreciation.

Gifts that are appreciated by nomadic families include both small tokens of friendship and also practical presents. Nomads in the remote areas of Mongolia rarely have stores nearby, are often on a tight budget, and they appreciate useful gifts. It is not necessary to bring large quantities – just a few items. We ask that you do not bring tobacco and alcohol for adults, nor sweets for children, for obvious reasons.

• Pens, notebooks, and notepads

• Something specific to where you come from – postcards, decorated tea towels, coasters, keyrings

• Fabric, scarves, warm socks, and gloves

• Small flashlights with batteries or wind-up torches

• Small pocket knives

• Sewing kits

• Pictures of the Dalai Lama or khatags, the Buddhist blessing scarves (get in UB), will be appreciated by older people

• Incense & Lighters

• Picture books, colouring books, stickers and pencils for children

• Hair bands and hairclips

• Small toys, such as farm animals, model aeroplanes

Shopping

Mongolia produces some good quality natural products, and traditional items. The most popular items are paintings, antiques, handicrafts, carpets, books, cashmere, traditional Mongolian clothing, musical instruments, Buddhist artifacts, leather goods, wall hangings, postcards, snuff bottles, and woodcarvings.

Throughout your trip you will have the opportunity to go shopping – from a roadside craft-stand selling yak wool products, to a cashmere factory outlet store in Ulaanbaatar. Our itineraries sometimes have shopping suggestions – but they are purely optional and you will never be taken shopping unless you have requested it or it has been offered as an option beforehand. In Ulaanbaatar there are a number of interesting shops, plus the usual standard tourist fare in souvenir shops. Your guide will be on hand to make suggestions if desired.

When buying any antiques, you need to be careful about what you buy as some of it is illegal. Make sure the shop you buy it from can produce a certificate of authenticity, as well as a receipt, in case you are asked for it by customs.

Bargaining – Most of the shops in towns have fixed prices which are often displayed on the goods. Do not try to bargain here. At markets, tourists are unlikely to be charged very much more than the locals, unless they are buying antiques, jewelry and other cultural items. By all means try and get a price down but be reasonable. For example, as a guide, don’t try for less than 60-70% of the asking price. And only start bargaining if you’re seriously interested in buying. Mongolians also don’t mess around, unlike their Chinese cousins. They’ll state a price to begin with, you then state a lower offer, and they will then generally state their lowest price that they are willing to go. You should, in most cases, take or leave it at that stage rather than trying to haggle further, as doing so will probably only frustrate or offend them.

Language

Mongolian is the primary language of Mongolia. Linguistically, Mongolian belongs to the Altaic family, which includes Turkish, Japanese, and Korean. Modern Mongolian, based on the Khalkh dialect, developed following the Mongolian People’s Revolution in 1921. The introduction of a new alphabet in the 1940s developed along with a new stage in Mongolia’s national literary language – including the assimilation of many Russian words.

Mongolians still use two types of writing: the classical script and the Cyrillic alphabet. The classical Mongolian alphabet, which is written vertically, is a unique script used by speakers of all the various dialects for about a thousand years. In spite of increasing interest in using only the classical alphabet, along with the decision by Parliament to use it for official papers, the majority of Mongolian people use the Cyrillic alphabet, which was adopted in the early 1940s.

Most Mongolians speak little or no English – especially in the countryside. At hotels, bars, shops and restaurants in Ulaanbaatar, most staff will have basic knowledge, and menus/signs are often written in English. Your guide and driver will teach you some basic phrases, but if you would like to come more prepared then please consult the ‘Further Reading’ section of this document for recommended language books.

Tips + Tipping

Tipping is quite a recent concept in Mongolia, but it is understood and appreciated. Drivers and guides will probably expect it, but only if they have earnt it! Here is some basic guidance, but please use your own discretion. If in doubt during your trip please ask your guide for advice.

+ Porters – It’s useful to have a small collection of $1 bills or 500 and 1000MNT notes for porters at hotels and ger camps.

+ Restaurants – Service is not included. Tips are not generally taken for granted, but if you’ve had a good meal with good service we suggest leaving 10% – always in cash, not on card as the staff probably won’t get it.

+ Airport transfers, city transport – In Ulaanbaatar you may have different drivers and vehicles than in the countryside, for practical reasons. It is not necessary to tip city drivers, and most wouldn’t expect it. But if you do feel that they have gone the extra mile (and I don’t mean taking the long way round!), then you could tip them $2-5pp for the day or equivalent in local currency.

+ Guides – A guide might ordinarily receive tips between $150-$400 in total for a trip lasting 10-14 days, depending on group size. So, let’s say you might budget between $50-$100 per person, depending on group size. On shorter trips, a calculation of $5 per day per person – based on a group of 2-4 pax – would be our recommendation. Solo travellers may want to increase it slightly.

+ Drivers – You will discover just how hard the drivers work, so tipping levels should not be far off what guides get. As an indication, budget 60-75% of guide tip allowance for drivers.

+ Others – Horse/Camel guides up to $5per day per person; Cooks on camping trips – similar to drivers (see above); Ger Camp staff, not at all necessary or expected but $1-5 here and there could be given at your discretion – for example, you may feel that a particular staff member at a camp deserves a little something. Perhaps they have been lighting the fire in your ger at dawn each morning, or have gone beyond the call of duty to help you or improve your stay.

Currency + Changing Money

The tögrög (or tugrik) is the official currency of Mongolia. It uses the sign ₮ and code MNT. There are no coins, only notes, with denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000, 10000, 20000. The exchange rate (as of January 2016) is 1USD = 1990MNT; 1GBP = 2870MNT; 1EUR = 2165

You can’t get MNT abroad – only in Mongolia. There are many banks, ATMs and exchange bureaus all over Ulaanbaatar, and some at the airport. Opening hours of the bigger bank branches are from 8 until 8, and some are 24hrs. Some close on Saturday, and all close on Sunday. You can also change money at the most hotels.

USD, GBP, Euro, Yuan, Yen, and other major international currencies (particularly Asian ones), are all fine to bring to exchange. But the best one is USD, because you can actually pay for certain things in USD – including tips (locals often prefer it). If bringing USD, make sure you bring crisp, clean notes, 2009 issue or later – otherwise most places won’t accept or exchange them.

+ Do NOT bring traveler’s checks. They are hardly accepted anywhere!

Spending Money

You are unlikely to need a great deal of money, as almost all our trips are inclusive of meals and most activities. On a 2-week trip, a budget of $400 should easily do, probably less if you are a couple or family. Roughly half may go on tips, and the rest on miscellaneous things like alcohol, and small trinkets, arts and crafts etc. that you might buy in the countryside. This doesn’t include any purchases you might make in Ulaanbaatar – e.g. cashmere, leather goods, traditional crafts – but these can be paid for on credit card, or by getting money out of the numerous ATMs around town.

Transport in Mongolia

Mongolia is a large country with a limited, though steadily improving, transport infrastructure. In many ways, the network of pot-holed roads, gravel trails and dirt tracks are an integral part of what make the country so appealing for travelers. Driving here is not a sanitised asphalt chore indistinguishable from your daily lives back home, but a predominately off-road overland adventure through diverse landscapes rich with wildlife and nomadic culture.

We recognize the need to balance the time it takes to drive anywhere with the time that you have available in Mongolia, and the need to experience, do and see. Unlike many companies, we do not advocate rattling along in a vehicle for 7 hours every day just to tick off points on the map from behind a car window. On our journeys, any necessary long drives are offset by photo stops, picnic lunches, roadside pitstops, tea/coffee breaks, and of course seeing points of interest, leg-stretching walks, dropping in on nomadic families, popping into villages and markets.

Consecutive days of long drives are rare – we prefer to stagger trips so that guests can enjoy and explore special areas where you really benefit from staying 2 or more nights, especially if you’re staying at one of our favorite ger camps.

To make the most of your time in Mongolia, we design itineraries which combine overland driving sections with domestic flights between Ulaanbaatar and far-flung areas of interest. The airlines we use are reputable companies with impeccable safety and maintenance records, with ever-growing fleets of modern aircraft. The majority of provincial destinations also have paved runways.

UAZ + Landcruisers

Our vehicle of choice is the UAZ. Fun, functional & practical, most of our guests fall in love with these indomitable vehicles and our fantastic team of drivers. With a high wheel base, large surround windows, ample luggage space, the flexible sociable layout comfortably seats 4-5 guests plus guide and driver. Quite simply, these beasts of the east were born for the wilds of Mongolia.

If your priority is comfort & air-con, and are prepared to pay a bit extra, then the Landcruiser is the perfect option. These vehicles are ideal if you’re travelling as a couple or as a smaller group looking for 2 or more cars to provide flexibility and privacy. Please note that, unless specified, we do not use Landcruisers for our group trips.

Domestic Flights + Baggage Allowance

There are 2 companies who operate domestic flights in Mongolia – Aeromongolia and Hunnu Air. There is not much to choose between them in terms of quality or service, so we tend to choose airlines according to scheduling preferences and/or availability. Domestic flights are operated using Fokker 50 and Airbus 319. The aircraft carry between 50-120 passengers depending on the type of aircraft and route flown.

+ During June-August there are twice daily flights to the most popular provincial destinations of Dalanzadgad (for Gobi Desert) and Muron (for Lake Khovsgol). During the off-season and winter months flights are much more limited.

+ Hunnu Air and Aeromongolia allow 10kg hold + 5kg hand luggage. Both airlines officially restrict hand luggage to 1-piece but this is rarely enforced. Excess baggage charges are between $2-5 per kilo depending on the route, so a few extra kilos isn’t going to break the bank.

Roads in Mongolia

The vast majority of Mongolia’s official road network, some 40,000 km, are simple cross-country tracks. Around 5000 km are graded, gravel covered or otherwise improved, but only 3500km are paved, although these latter two figures are increasing as the government is investing heavily in creating better road links between the main provincial centers and the capital.

Accommodation in Mongolia

From the warmth of countryside hospitality, and the novelty of sleeping in a traditional ger, to the laid-back character of the capital’s service culture, the accommodation Mongolia has to offer is diverse. Enjoy the relative luxury of lodge-style countryside retreats and Ulaanbaatar’s modern hotels, plus homely and endearing rural ger camps, and other more rustic options – including homestays and camping.

Our Mongolia agent regularly reviews and researches the accommodation choices to ensure that guests are provided with the right balance of style and substance, with local flavou and character. The various overnight stays in Mongolia will offer variety and interesting experiences, mostly tremendously enjoyable and memorable.

Hotels in Mongolia

On most journeys you will spend your first and last night in Ulaanbaatar, often by necessity as well as by design. Like any rapidly developing metropolis, traffic, noise, and pollution are all issues – so location is key. We have a preferred list of hotels that balance character, atmosphere, service, cleanliness, and comfort – all within convenient well-lit walking distance of the city center.

Ger Camps

Outside of the capital, you will spend some – or perhaps all – of your nights at ger camps. These are locally-run enterprises set in rural locations near areas of cultural, historical or geographical interest. A ger camp typically comprises 20-30 gers, each with 2-4 beds and a traditional wood-burning stove. Separate male & female bathroom blocks with western-style facilities are located a short distance away, as well as a communal larger dining ger or lodge where meals are served.

Facilities can vary from civilized to basic. Some camps have 24hr mains electricity, hot water on demand, plus lighting and plug sockets in the gers. Others have no mains electricity, but have generators that operate only at certain hours. Hot water is often only available at certain times, and even then it is not guaranteed. Extra services are provided by many ger camps – laundry, massage, sauna, equipment hire (e.g. fishing rods, kayaks etc. at Lake Khovsgol). Unless otherwise specified in the itinerary, the costs for these are extra.

Homestays

Many itineraries include homestays with local families where you can experience Mongolian life up close. Stay in a guest ger, learn their customs, and enjoy traditional cuisine.

Camping

Activity based wilderness trips will mainly consist of wild camping. Some with vehicle support, others with pack animals and a more pared down equipment quota. Our Mongolia agent supplies all camping and cooking gear except for sleeping bags which can be rented at a small additional charge.

Food in Mongolia

We guarantee that you will be pleasantly surprised by the food available in Mongolia. This is partly because your expectations will be low, but also because, contrary to popular belief, dietary options are not just limited to mutton and fat. In Ulaanbaatar, there is a range of great local and international restaurants, and although in the countryside the choice and ingredients are more limited, there are some traditional culinary specialties to enjoy and savor.

Ger camps have set menus (for example, cucumber & tomato salad, beef goulash, fruit compote). Traditional cuisine is served but often with a twist or refined to suit Western tastes. Russian influences are stronger than Chinese, although both feature.

We cater for all dietary needs (vegetarian, vegan, dairy, wheat free, etc). We like to vary meals during a trip – lunch may be with a nomadic family, or at a roadside cafe, or a picnic. Each vehicle is also kitted out with a snack box – chocolate, crisps, nuts, dried and fresh fruit. We often also stop and stock up on supplies at local villages and markets.

In summer, delicious local homemade yoghurt, clotted cream and wild berry jams are also available – often from nomadic families, but also at ger camps. Although mainly imported, a growth in organic farming has led to an increase in availability of fresh fruit and vegetables.

Water

We include an unlimited supply of still mineral water on all trips which involve overland travel in vehicles. We provide small bottles and also large containers from which we fill the small bottles from. This enables us to reduce the amount of plastic we use. Wherever you stay or eat, they will not mind you bringing in your own bottled water, so we advise stocking up from the vehicles each night to avoid you having to pay unnecessarily for water.

For adventure trips, during sections without vehicle travel (i.e. walking, on horseback), we either provide water filters which enable you to fill up your bottles at streams and rivers, or we boil enough water each morning for you to carry in your daypacks and drink as you go along.

Soft Drinks + Alcohol

We provide a complementary ‘starter pack’ selection of soft drinks and alcohol on all trips – but once these supplies have gone you will need to stock up yourselves, if desired. Ger camps have bars – some well-stocked including an array of soft drinks, mixers, drinkable wines, spirits and cold beers; and others less well-stocked, often just with fruit juice, vodka and room-temperature beer. The former tend to disapprove of – or not allow – guests bringing in their own drinks (other than water); but the latter tend to accept that guests will bring in other drinks to supplement their own poor selection!

Stocking Up

There are plenty of opportunities on most trips to stop in villages and towns en route to stock up on extra drink supplies if needed. Choice in the countryside is more limited than in Ulaanbaatar, so if you know you have a penchant for a specific imported soft drink, gin and tonic, a good red wine, or a nice whisky, then visit a supermarket in Ulaanbaatar at the start of your trip or the Duty Free shop before you arrive.

Local Drinks

Mongolian tea is the local drink of choice – traditionally made in a large pot over a stove with half-water, half-milk, a handful of tea leaves, some salt, and perhaps a dollop of butter (or fat left over in the pan).

In the summer months, airag – fermented mare’s milk – is widely available in the countryside. The fresh milk is stirred and aerated over a period of 2-3 days until it starts to ferment. A ‘young’ airag will taste light, slightly sharp and lightly fizzy with a very slight alcohol content (0.5%)- not too unpleasant. An ‘older’ airag – a week or two old – will taste rich, sour and fizzy, with a slightly higher alcohol content – this is an acquired taste!

There is a wide variety of Mongolian beer – much of it very good, partly due to the German-invested breweries and equipment. The classic Borgio lager is a national staple, as well as Sengur, whilst the pilsner style Chinggis and Golden Gobi offer a more robust flavour, and darker brews such as Khar Khorum add further variety. No mention of drink would be complete without vodka – Mongolians drink a lot of it. Most is poor quality, but some (like Bolor) is very good. Nomads distil their own ‘milk’ vodka, which is around 10-12% and is surprisingly drinkable.

Responsible Travel | Goyo

From our excellent Mongolian Agent: The concept of responsible travel is highly subjective, a turn of phrase that is overused, often misunderstood and under implemented, both by travel companies and travelers alike. At Goyo Travel we don’t pretend to be whiter than white, nor do we make overblown claims about our ethical credentials, nor use hackneyed quotes by historical figures and pretend we live by their mantras. What we are though is honest, fair and transparent, whilst doing our best to reduce our environmental impact and give back to the communities that we visit.

Local + International Perspective- We strive hard to make sure that any cross-cultural interaction or transaction is mutually beneficial. We pay locals a good wage – from our office staff, through to our guides and drivers, right down to nomadic families providing a meal or horses for rent. We also charge our guests what is fair – not what we can get away with. Thus closes the gap between expectation and reality, and everyone comes away satisfied. We also invest in people’s futures and livelihoods – from simple things like paying tax and social insurance, to training and education of local staff and partners, cross-fertilisation of ideas to improve the Mongolian tourism industry, and creating new sources of income for nomadic families such as homestays or recruiting rural family members as cooks/assistants.

In tandem with our environmental concerns we also endeavour to source, where practical and available, a good proportion of equipment and provisions that are 100% Mongolian. A Mongolian biscuit can be equally as good as a British one, the difference being that it hasn’t travelled 6,000 miles to get to you. Conversely, we also recognise the importance of imported goods bought by us in Mongolia, especially when there is not a suitable locally-made alternative – in these instances, quality combines with the added benefit of international investment in the country’s economy and employment.

Environmental Travels | Goyo

We recognise that the environmental impact of travelling to Mongolia is considerable and it’s not realistic or practical to think it can be completely offset in a vain attempt to clear our conscience. However, we can do our best to mitigate the damage. Here’s a list of measures we take to do our bit for the environment:

– We carry 20 L containers of water to refill smaller bottles, thereby reducing the amount of plastic waste

– We dispose of rubbish in large towns rather than rural areas, as otherwise it often ends up in unsightly and environmentally damaging open landfill sites in the open countryside on the edge of villages.

– A percentage of all our revenue goes to support environmental projects such as Gobi Oasis, a tree-planting nursery in Mandalgobi that fights against the increasing desertification – www.gobioasis.com

– We do not drive distances that are better walked, unless weather or guest fitness does not allow. This is particularly applicable in Ulaanbaatar where the traffic is horrendous – walking is not only by choice but also necessity!

– We request our staff pick up litter in rural areas if they come across it, sometimes encouraging guests to join in too! Litter is an all-too-common problem in a country where non-degradable food and drink packaging was almost non-existent 20 years ago, and its increase has sadly not been matched by environmental policies and education.

– We streamline our logistics. For example, if a driver needs to get to or from a remote pick-up or drop-off point for domestic flights, then we endeavour to manage different trip bookings so their drivers finish one job in the same place they start the next. If not possible, we make sure they don’t drive empty – instead carrying equipment, staff and/or local passengers as a public transport service.

– Behind the scenes, we do what we can in the office, including walking to work; printing only what we have to, and on recycled paper or on back of used paper; doing bulk shopping at wholesalers every so often rather than regular car journeys to supermarkets.

Local Community Projects | Goyo

Our Mongolian Travel Agent believes that supporting local community projects and charitable foundations is important – as part of our collective contribution to cultural, social and environmental regeneration. However, we like to combine financial donations with personal investment of time – with visits and active involvement in projects giving an insight into the work they do and delivering a more meaningful experience for both sides. Here’s are just a couple of examples of how we do this

Women’s Quilting Centre – We support this group of previously disenfranchised ladies who have turned their skills to needlework, using a variety of quilting techniques, combined with traditional Mongolian design, to provide a great selection of handicrafts. We visit their workshop and outlet on most trips, use many of their products, and can offer guests the opportunity to spend a day learning techniques and making traditionally designed items. All monies go directly to the project.

Gobi Oasis – Byamba has been running the Gobi Oasis tree nursery tirelessly for over 35 years, planting seedlings to combat desertification. The project is located on the edge of the provincial town of Mandalgobi, and on many trips we stop by for an overnight stay in with Byamba’s family, with a visit to the nursery to plant some seedlings. We also take volunteers to work at the nursery for periods of 1 -6 weeks and longer. All monies from these visits go directly to running of Gobi Oasis.

Photography in Mongolia

Many people travel to Mongolia for the photographic opportunities that the country offers – whether you are interested in landscapes, portraits, architecture or photo-journalism. All our itineraries are very flexible, building in time for unplanned photo stops, and taking advantage of sunrise and sunsets in key locations.

When it comes to photographing people, Mongolia is generally no different to other countries in the world – most people don’t mind having their photo taken, but some don’t. But either way, unless you are being discreet and at an unintrusive distance, please ask permission before you do it. Unless, they ask you first of course! This is also quite common particularly in rural areas or at festivals and other times of celebration when people love to have their photo taken, especially if they are in full traditional costume. On such occasions, the value of having a Polaroid camera is immeasurable, so it is definitely something to consider – particularly if you are likely to travel regularly to other countries where you might benefit from having one.

Photography is generally not permitted inside temples and museums, although many will allow it for a fee – usually around $5 or so for still shots, and more for video. These costs are not included in any itinerary and must be paid in cash.

Employ a degree of care and sensitivity when taking scenes of everyday life – particularly in villages and markets, as people do not like feeling as though they are being objectivised or degraded. Also be sensitive about taking pictures of things that to Mongolians may seem odd for you to want to photograph – for example, a carcass of a camel at a market may be a novelty sight for any visitor, but to them it would be like you seeing someone in your own country taking a picture of chicken in a supermarket (for which you’d certainly get some odd looks!). In all these situations, perhaps explain why you want to take such pictures, so they understand your motives. If in doubt, ask your guide. They will be able to advise, negotiate special permission in places if necessary, and also translate on your behalf.

Photography Tips | Goyo

– Bring a polarizing filter to cut the glare on sunny days.

– Cotton buds are useful for cleaning hard-to-reach areas in dusty conditions

– Large, heavy-duty garbage bags or ziplocks can be useful to protect your camera in inclement weather.

– For travel in wet conditions, you might want to consider bringing a dry bag or Pelican Case.

– Please be particularly careful in the Gobi, as both dust and sand are plentiful and can wreak havoc on cameras

– Bring a spare fully charged battery if on a remote expedition, as charging opportunities could be limited.

Communications in Mongolia

UB | Connection 24/7 – During your time in the capital, you should not have a problem with communications. Foreign mobile phones, iPhones, iPads, tablets and android devices should all work to make telephone calls – and usually also receive e-mails and internet connection. However, if these services aren’t working, or you don’t have an internet-enabled phone, many hotels and cafes have wireless broadband, which can obviously be used with laptops as well. Hotels also have business centres with desktop computers, internet, fax, printer, and copying services. There are also phones in the hotel rooms.

Countryside | Mobile Phones – During your time in the countryside, communications will be more limited. Mobile coverage is increasing every year, even in rural areas, so you and/or your guide will have access to mobile phone reception at some time on most days.

Internet Access | Internet access will be restricted to larger towns and villages which you will have the opportunity to pass through every few days – these will have internet cafes, often with slow connection (and also affected by sporadic power cuts). We advise all guests that it is best just to plan for no internet access whilst you are in the countryside.

Satellite Phone | We provide some trips with a satellite phone, depending on the remoteness of the route and/or activities and the associated risk involved. Your itinerary inclusion/exclusion sections will indicate whether or not your trip includes provision of a satellite phone. If it does not, and you would like one to be provided, please ask us in advance of your departure and we can arrange satellite phone rental at a small additional cost.

Mongolia

Mongolian Greetings

The best advice my friend photographer and writer Michael Benanav who spent three months exploring Mongolia had for me was to ‘Let it all go’ and learn the phrase for ‘Call off the Dogs’!

Mongolia

Mongolia (or Outer Mongolia), a vast country in the heart of Central Asia referred to by its inhabitants as ‘Blue Mongolia’, is a country of eternal blue sky, nomads, yurts, desert and extreme contrasts. Protected by an immense blue dome, the Mongolians revere nature and the heavens and their protectors. To this day, Mongolian women offer the first sip of their milky tea to the sky gods.

Mongolia, its meager population (which has quadrupled since the turn of the century) of 2.7 million living in an area half the size of Europe, is sandwiched between Russian and China, and was caught in a tug-of-war for many years with Russia winning out. In 1990 Mongolia became democratic and instituted numerous political reforms; after many years of being closed, its now open to the outside world and it welcomes tourism but with a more basic infrastructure than other Asian countries in general. Twelve hundred years ago the nation we now know as Mongolia was made up of nomadic tribes, but now only half of the population continue their nomadic lifestyle, the other half living a much more modern life-style in cities and towns. The nomads produce approximately 20% of the Pashmina wool sold on the world-wide market.

Before the onset of communism when all but one monastery were destroyed and nearly half the monk population killed, Mongolia was second only to Tibet as a strong-hold of Tibetan Buddhism. Since the liberalization in the 1990s there has been a huge revival of Buddhism, and Mongolia now hosts over 130 Buddhist monasteries. There are also approximately 60,000 Kazakh Muslims and a small percentage of Christians in Mongolia.

The topography of Mongolia ranges from the Gobi Desert to high mountain ranges to the severe Siberian steppe …

Altai Mountains

The Altai Mountains, the largest chain in Central Asia, guard the farthest western reaches of Mongolia, at the point where China, Russia and Mongolia meet. The Tavan Bogd or ‘Five King Peaks’ are the highest peaks in the Mongolian Altai range, the highest reaching over 4000 meters. In the summertime, the region is full of colorful wildflowers. Kazakh and Uriankhai nomads roam the plains with their flocks of sheep and herd of horses, camels and sometimes even yaks, living in their traditional yurts, called gers in Mongolia. The Muslim Kazakhs are famed worldwide for hunting with their Golden Eagles. The Uriankhai are Buddhist, and hunt in a more traditional way with bows and arrows.

Kharkhiraa Uul and Turgen Uul are twin peaks dominating the western aimag, home to the Khotan nomads, famed throughout Mongolia as shamans, grazing their flocks in the summertime.

Khovsgol Lake